- History for Peace

- Jul 12, 2021

- 8 min read

A video recording of the session and the PPT used therein are available on request. Please write to us at info@historyforpeace.pw for the same.

Introduction

In the second session of the Beyond the Textbook series, Medhavi Gandhi brings us avenues to encourage students to reflect on the practices, languages and creative legacies of the Indian subcontinent through analysis of a selection of objects from the Partition Museum in Amritsar. This segment hopes to help students draw cross-cultural connections, recognize the important ways in which our pasts have contributed to a rich diversity and to bring in the question of Identity and how it can be impacted by experiences of migration, whether our own or our preceding generations'.

Along with the recording, here, we share a few ideas on classroom activities based on sections of her talk. However, for an in-depth understanding we recommend watching the video recordings of her sessions before implementing any of these in the classroom.

MIRZA GHALIB

Is Language Secular?

Celebrated on both sides of the border, Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan, also known by the pen names Ghalib and Asad, is a cultural icon who lived much before the Partition happened. Yet, his poetry remains as relevant today as it was when he wrote it.

Ghalib started writing poetry at the age of 11. Urdu was his primary language, but Persian and Turkish were also spoken at home. His education was in Persian and Arabic. At the time Hindi and Urdu were synonyms, unlike today. Ghalib wrote in Perso-Arabic script which is used to write modern Urdu, but often called his language ‘Hindi’.

Reading Ghalib’s poetry you realise that language has no religion and that understanding Urdu does not necessarily need you to be a Muslim. His was a language of Delhi.

[In Delhi] Urdu really developed as a result of Persian, Turkish, Dari and Pashto interacting with other local dialects like Braj, Mewati, Haryanvi, Punjabi, Rohelkhandi, Bundelkhandi, Malwi and other indigenous languages that gave way to a certain kind of Urdu. The Urdu in Lahore—a lot of authors who have studied Partition have also shared that Urdu in Lahore today is much more heavier than it was in Delhi at that point in time. It was much more refined. Some words for example have got completely lost.

The idea that we come to is that with the Partition, the culture of Delhi starts to get overshadowed with the newer sensibilities that are coming in. And this is the tricky part. How do we recognise those? How do we recognise the change that comes in slowly, whether it was in food, the dressing or language? Slowly, our culture starts to change and we come to the big question—how does modernity accept tradition. How is society shaping with the new beliefs, the new shifts, and what factors influence identities in this changing scenario?

-Medhavi Gandhi

His works help us explore the link between language and identity.

ACTIVITY / ASSIGNMENT IDEAS

I. What do you know of the poet Ghalib?

Divide the class in groups and assign each group one of the following categories to research:

Ghalib’s ancestry

Important milestones in his life

Most well-known writings

Political and religious beliefs

His contemporaries

Legacy on both sides of the border [how is he remembered in India and Pakistan: commemorations/monuments/publications etc.]

II. What do you understand from ‘Hindi’ and ‘Urdu’? Are these languages unchanged from what they were 150 years ago? Find out.

III. Share the following list of words with your students and ask them to identify which language/s they belong to:

IV. Identify Urdu words from contemporary Bollywood songs and make a list. Attempt to use this list of Urdu words in a conversation.

V. Ask students to read the following poems by Ghalib, both in Urdu [Roman Script] and in English translation. Is there a difference in their listening experience?

Hazaaron khwaahishein aisi ki har khwaahish pe dum nikle,

bohot nikle mere armaan, lekin phirbhi kam nikle.

‘I have a thousand desires, all desires worth dying for, though many of my desires were fulfilled, majority remain unfulfilled.’

Dil-e-Naddan tujhe hua kyahai? Aakhir is dard ki dawa kya hai?

‘Oh naive heart, what has happened to you? What is

the cure for this pain, after all?’

Allah Allah Dilli Na Rahi, Chavni Hai, Na qila, nashaher,

na bazar, na nahar; Qissa mukhtasar – shahar Sahra ho gaya...

‘Oh Lord! Delhi turns into a cantonment, devoid of

cities, markets, rivers and forts.’

matā-e-lauh-o-qalamchhin-gai to kyāghamhai

kekhun-e-dil men dubo-li hainungliyān main-ne

zabānpemuhrlagihai to kyā, kerakh-di hai

harekhalqa-e-zanjir men zubān main-ne

‘Why bother that the tablet and the pen are seized?

I have dipped the fingers in my heart’s blood.

Why bother that the tongue has been silenced?

I have placed my tongue in each of the fetters’ rings.’

MURAQQA-I-CHUGHTAI

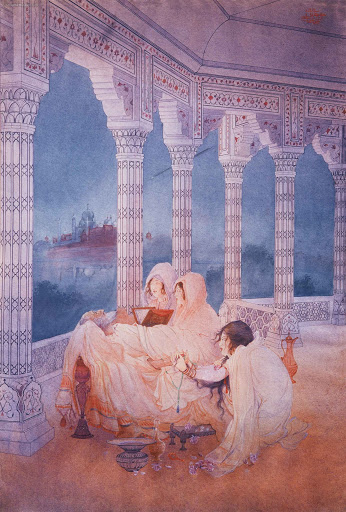

The Muraqqa-i-Chughtai is part of the collection of the Partition Museum. Published in 1927, Muraqqa-i-Chughtai is an album of paintings that visualise Ghalib’s poetry.

A.R. Chughtai, like Ghalib, is celebrated in India as well as Pakistan. Born in Lahore, he is the national artist of Pakistan today, but that does not in any way take away from his legacy this side of the border, in India. He is hailed as one of the most important artists of the twentieth century.

Many art historians today talk about Chughtai’s works speaking of a ‘shared heritage’. But during his time there were no divisions, there was no concept of this is mine this is yours. It is post partition that the concept of ‘mine’ and ‘yours’ gains importance.

A lot of his work borrows from the Miniature tradition. There is also the influence of Japanese Calligraphy technique—something he picked up while he was visiting the Tagores in Calcutta.

- Medhavi Gandhi

'Chughtai’s visualization of Ghalib’s poetry is a reminder of the Ragmala-painting tradition. In ragmala paintings, artists usually visualize the mood of a raga . . . Chughtai combines the lyrical medieval miniature style with a modern technique.

In Ghalib’s time, his contemporaries found it difficult to even understand his poetry. To visualize his wit, therefore, is a feat few could have achieved. It is no wonder that the book was thought to be the finest in publishing at the time. The Maharani of Cooch, Behar is said to have partially funded this project, and it is believed to be a dedication to the Nizam of Hyderabad.'

ACTIVITY / ASSIGNMENT IDEAS

The image to the left is sourced via www.heritagelab.in; The image to the right is sourced through Wikimedia Commons.

I. Share the above two images with your students.

The one on the left is by A. R. Chughtai and the one on the right is by Abanindranath Tagore. Both these paintings depict ‘The Passing of Shah Jahan’.

Which painting are students more drawn to and why?

As conversation around Nationalism was gaining momentum, both these artists, you can see in their works, were making a conscious move towards rejecting what the British academic style of art was—focussing on what our legacy, which could be traced to the pre-colonial Mughal era, is.

- Medhavi Gandhi

II. Divide the class in groups. Ask each group to identify one painting each of A.R. Chughtai and Abanindranath Tagore that represents the politics of the time and prepare a presentation that addresses the following:

I noticed . . .

I wonder . . .

I was reminded of . . .

I think . . .

I’m surprised that . . .

I’d like to know . . .

PHULKARI

Region: Phulkari is an embroidery style that originated in Punjab. It is used and embroidered in different parts of Punjab namely Jalandhar, Amritsar, Kapurthala, Hoshiarpur, Ludhiana, Ferozepur, Bhatinda and Patiala. The earliest available article of phulkari embroidery is a rumal embroidered during fifteenth century by Bibi Nanaki, sister of Guru Nanak Dev. The needlework is widely practiced by the women of Punjab and holds significance in the life of a woman, from her marriage till her final abode to heaven.

Technique: The base material to execute Phulkari is handspun and handwoven khaddar that is dyed in red, rust, brown, blue and darker shades. Soft untwisted silk thread ‘Pat’ is used for the embroidery. The colours of the thread are red, green, golden yellow, orange, blue, etc. The basic stitch employed for Phulkari is darning stitch, which is done from the reverse side of the fabric. The stitches follow the weave and a beautiful effect is created on the fabric by changing the direction of the stitches. For outlining of motifs and borders, stem, chain and herringbone stitches are sometimes used.

Style of embroidery: The two embroidery styles prevalent in Punjab are Bagh and Phulkari. Bagh is a fully embroidered wrap that is used for special occasions whereas Phulkari is simple and lightly embroidered for everyday use.

Motifs: The motifs used in Phulkari are inspired by objects of everyday use like rolling pin, sword, flowers, vegetables, birds, animals, etc. They are generally geometrical and stylized. Usually one motif is left unembroidered or is embroidered in an offbeat colour. This motif is called ‘nazarbuti’ which is considered to ward off the evil eye.

End use: Phulkari is an important part of the bridal trousseau and is worn as a veil or wrap by women on special occasions like Karva Chauth, a festival celebrated in North India for longevity of husbands. A specific pattern of Phulkari is also used as canopy on religious occasions. Presently, Phulkari is being done on bed linen and apparel like tops, tunics and skirts.

-‘Embroidered Textiles of India’, Traditional Indian Textiles, Class XII, CBSE.

Phulkaris were of different types. Some showed geometric patterns, some didn’t. A lot of textile historians have later assumed that the ones that are geometric in pattern could have been made by Muslim women because they don’t replicate God’s creations, so they don’t make any human or animal figures. Phulkari was something that you just got together and then created. You sang songs and created—the songs you sang, the little moments of gossip, all those stories sort of defined what you are going to make on that particular chaddar and gift (these were gifts you gave on family occasions). There were also phulkaris created for religious purposes but largely they were very personal and private in nature until after the Partition when they started being revived for commercial purposes. The cloth is khaddar, silk threads—a lot of the raw material required for making phulkari came along the trade route that had already been established through Afghanistan, or via Bengal. For instance, silk threads often came in from China. After the Partition all of this changed, because the access to these materials underwent change. BawanBagh—52 motifs—the idea was that the motif was shared within the regions. You look at the stitch—if it was a darning stitch at the back, it was probably someone from a well off family. If it was a cluster stitch at the back, maybe it belonged to someone who wasn’t so well off . . . the khaddar was stitched after the embroidery in Pakistan, it was stitched before the embroidery in India.

-Medhavi Gandhi

ACTIVITY / ASSIGNMENT IDEAS

I. Ask students to collect images of diverse examples of Phulkari. Divide the class in groups to list the differences they spot in each of the image with regards to the embroidery technique and the patterns.

Once they have discussed the differences encourage them to analyse the below statement.

A lot of textile historians have later assumed that the ones that are geometric in pattern could have been made by Muslim women.

-Medhavi

II. Get students to create a map of the subcontinent based on different handicrafts.

Identify the crafts that were adversely affected by the 1947 Partition and analyse the

reasons behind the adverse affects.

III. Get students to put together a small museum of embroideries based on what they

find within their own families/communities, along with narratives on/histories of the

same.

Comments